Story and characters

De bello gallico is an opera that uses the figure and the feats of Julius Caesar to address the mechanisms of power, self-congratulation, mass seduction and war in a gentle tone. In places, it almost resembles an opera buffa, but there are moving and dramatic moments too.

The libretto is adapted from Commentarii de bello gallico, one of the most famous books of all antiquity, Consul Gaius Julius Caesar’s firsthand account of the long series of campaigns he fought from 58 to 49 BC to conquer Transalpine Gaul. In the aftermath, he became one of the most celebrated, admired and feared men of his time.

Twelve years of war, in fact, not only led to the conquest of a huge territory, rich in resources and men, but also earned the general one honour after another. We might even be tempted to think that Caesar, still a consul, was already planning to use the conquest of Transalpine Gaul as a springboard for achieving even greater power. The fact is that he subsequently found himself projected by his successes towards absolute power and leadership of the ancient world.

De bello gallico is, on the one hand, a celebration of the condottiere’s exploits written in the dry language of a military report and, on the other, a text that established the greatness of the future dictator perpetuus of Rome as one of the most famous historical personages of all time. Alas, it also served as a model for many of the dictators who were later to tread the historical stage.

In the opera, Caesar embodies two figures alternately.

The first manifestation is the Caesar of tradition: the historical personage and the unscrupulous politician who is building an image for himself by telling the story of his deeds. He addresses the audience directly, declaiming from a sort of podium – sometimes akin to the ones used by contemporary politicians – other times like the plinth of a monument from which the character protrudes like a marble bust.

The second figure is Caesar the human being: vain, intelligent, a clever manipulator, ruthless with his enemies (but also with any Romans who are not faithfully on his side), keenly engaged in alliances and intrigues, impassive but neurotic and a victim of splitting headaches. This second Caesar does not use the third person or the past tense, but lives in and relates to a present charged with tension, danger and urgency. When he drops this ‘official’ guise, he leaves the monumental podium to speak and argue directly with the chorus, recounting the events of the wars in the present as if they were happening before his very eyes. Like a flashback in a film that becomes so vivid, it morphs into a kind of hallucination.

Moving around the leading player, the male chorus represent alternately his multitudinous legionaries (epitomized by his beloved Tenth Legion), indefatigable fighters, amazing engineers, highly disciplined, deadly soldiers, and the Gaulish masses who Caesar defeated, humiliated and ultimately wiped out.

On stage with them is a soprano, an allegorical Figure who surprises everyone by representing different characters – from Fortune to Glory to Rome, amongst others – depending on the circumstances.

There is also a tenor. In the first act, he plays Caesar’s scribe, Aulus Hirtius, whose job it is to write up De Bello Gallico. In the second act, instead, he takes the role of Vercingetorix, first an icon of Gaulish resistance, then a slave in chains by Caesar’s tent.

In the epilogue, the general returns to the scene in emperor’s robes, but bloodied. Caesar tells of the few years he lived before the conspiracy – ten years lasted the campaigns in Gaul, but only five were enough for Rome to kill him. Now that his destiny had been fulfilled, now that he was an emperor – first honored as a god and then assassinated – in his memory the most poignant period remains the one recounted in De bello gallico: the years of battles in the company of his legions, of peoples known and vanquished, and of summer campaigns during the month that still bears his name – July.

Press

In questa nuova opera, su libretto di Piero Bodrato (con cui il fecondissimo Campogrande ha concepito anche altri titoli: Opera italiana del 2010, Folon del 2017 e La notte di san Nicola del 2020) Cesare è rappresentato in chiave eroicomica: viene quindi rispettato il format dell’opera buffa, in due atti, con recitativi, arie, cori, duetti e concertati, dove non mancano però momenti di riflessione drammatica sugli orrori di tutte le guerre espressi con immagini anche forti; molti i riferimenti ai “popoli stuprati dalla storia” e umiliati dagli invasori, al deserto e alla distruzione in nome di quella che viene chiamata “pace”, che rimandano alla tragica attualità. Per il resto il libretto è divertentissimo, tutto un tripudio di trovate, doppi sensi, citazioni colte, miscugli di latino e italiano, assonanze, nel rispetto della metrica operistica classica in endecasillabi e settenari con giochi musicali di rime interne e allitterazioni. […]

Come il libretto si presenta ricco e intrigante, così la musica è complessa, mai banale; l’orchestrazione, a tredici parti, è ricca di impasti timbrici, con uso spiccato degli ottoni e delle percussioni, ma anche dell’arpa. Emergono diversi registri linguistici: profili melodici che si stagliano sul declamato vocale e che vanno a delineare vere e proprie arie, o duetti come quello, bellissimo, tra Cesare e Vercingetorige che si rimpallano i versi “moriám da eroi/moriám da coglioni”; in alcuni casi si avvertono incursioni nel linguaggio della pop music e del jazz, sia per lo stile del melos, sia per l’uso marcato di sincopi e contrattempi e del basso elettrico. […]

Il pubblico, numeroso, ha molto apprezzato l’opera ed ha applaudito a lungo gli autori e gli interpreti.

– Lucia Fava, Il Giornale della Musica

Una brillante narrazione buffa che sembra quasi guardare allo stile e all’esempio delle opéra-bouffes di Offenbach nel mescolare mito antico e riferimenti espliciti alla modernità, confezionando uno spettacolo gradevolissimo e frizzante, in cui l’economia dei mezzi utilizzati (solo tre i cantanti in scena) non ha impedito all’esecuzione di coinvolgere e divertire il pubblico di studenti delle scuole superiori che per l’occasione ha riempito il teatro. Lo spettacolo di Tommaso Franchin ha riletto la vicenda, che non aveva alcuna pretesa di verità storica già dal libretto di Piero Bodrato, in maniera brillante, applicando la metafora della guerra come un incontro di boxe all’intera narrazione che, grazie alla vivace direzione di Giulio Prandi e alla bravura del cast, si è snodata fluida e leggera, riuscendo a coinvolgere e divertire. Molto bravo Giacomo Medici nel ruolo di un Cesare impegnato a essere influencer di sé stesso, costruendo la propria fama e la propria immagine di guerriero e condottiero, ma è stato notevole anche Oronzo D’Urso come Aulo Irzio e Vercingetorige e Nikoletta Hertsak ha sfoderato il giusto charme nei panni della Figura Allegorica, peraltro spesso chiamata a esplorare le zone più estreme del pentagramma con sovracuti di sicuro effetto spettacolare. Pubblico molto festoso per un’opera che meriterebbe bene di girare perché molto leggera e deliziosamente divertente.

– Gabriele Cesaretti, MUSICA

Il libretto di Piero Bodrato è liberamente derivato dai “Commentarii de bello gallico” , dove si raccontano le imprese militare che portarono Gaio Giulio Cesare a conquistare la Gallia Transalpina. L’autore riesce a parlare del passato con un’attualità disarmante, condannando il potere, l’autocelebrazione, la guerra, la seduzione delle masse. E lo fa con uno stile asciutto, con intelligenza, con pungente ironia e sottile comicità.

La partitura di Nicola Campogrande è suggestiva e interessante, ricca di contaminazioni che vanno dalla cantabilità dell’opera lirica al tango, allo swing, al flamenco. Le parti corali sono in bilico tra un canto antico di tipo modale, diatonico e quello più pop del musical.

– Marco Sonaglia, OperaTeatro

De bello gallico in prima assoluta al Pergolesi di Jesi sorprende e convince.

– Stefano Fabrizi, Marche Infinite

De bello gallico, “opera buffa” che ci consegna profonde riflessioni storiche La prima mondiale al Teatro Pergolesi. Melodie caleidoscopiche e travolgenti.

[…] Testo molto bello, mai banale e, volendo, scanzonato, attualizzato con uso di termini gergali e bandiere giallorosse con “Forza Roma” attuali che fanno anche ridacchiare più che sorridere soltanto. […] La musica scritta da Nicola Campogrande, che spazia come se avesse un brevetto di volo adatto per le lunghe distanze, scandisce i momenti di vita con atterraggi simulati e poi ripartenze improvvise, da Gershwin al tango, dalla musica americana, dal jazz alla tradizione dell’opera buffa che ti fa venire in mente Rossini. Ma solo in mente. E poi valzer e poi lirica drammatica o codificata. Un caleidoscopio in cui il pubblico non si perde, anzi riesce a vivere accanto alle figure che Cesare incarna. Nella prima parte, è l’uomo politico e spregiudicato, che ha voglia di fare carriera e ha in Aulo Irzio il suo scriba, ma anche il consigliere per gli abiti da indossare […] La seconda essenza di Cesare è quella che affronta il pericolo, manipola ed ammazza avversari e, alla fine, il dado viene tratto e lui venne, vide e vinse. Accanto, una bellissima donna, una figura allegorica che rappresenta una volta la Fortuna, la Gloria, Roma, quello che Cesare ha vissuto realmente nella sua vita. Non stiamo a raccontarvi il libretto e la storia che Cesare Caio Giulio ci ha costretto a studiare. E che arriva fino a noi, vedete la forza dei personaggi che attraversano duemila anni e sono ancora attuali.

– Giovanni Filosa, Qdm Notizie

[…] vede sì Giulio Cesare quale protagonista in musica delle sue avventure di conquista in terra gallica, ma in una focalizzazione scenica del tutto diversa, immerso com’è in un palese clima d’ironia, più sottilmente irridente appunto che serio, rispetto alla ricercata oggettività dei fatti narrati da parte dello storico autore dei “Commentarii”, e dove lui stesso com’è noto parla in terza persona. […] Un canto degli interpreti variegato nella melodia, nella recitazione ritmica in stile “Sprechgesang” schönberghiano e in altro. Un saggio operistico nuovo e singolare, che merita comunque di essere visto.

– Fabio Brisighelli, Corriere adriatico

Il racconto ufficiale è in terza persona, ma Nicola Campogrande, autore della musica (su libretto di Piero Bodrato), porta in scena anche un Cesare più quotidiano che si rivolge al pubblico direttamente. Da un lato il generale vittorioso, dall’altro l’uomo con i suoi problemi. […] In scena la Fortuna con i suoi alterni rovesci, non esita a passare dalle braccia di Cesare a quelle più muscolose del suo antagonista Vercingetorige.

– Damiano Fedeli, RAI Tg3 Marche

Non è mancato niente: grandi arie per Giulio Cesare, sempre in scena; una sapiente, bene intessuta polifonia per il coro; escursioni vocali da capogiro per la Figura Allegorica, che canta come una fata; un tramutamento camaleontico per il tenore nel doppio ruolo di Aulo Irzio e di Vercingetorige. […] Lo spettacolo ha tenuto sino all’ultimo l’attenzione del pubblico, che ha mostrato stupore di fronte a un’opera così originale e magari un po’ sconcertante per l’immagine inedita di Giulio Cesare. […] Fa sorridere, meditare, sorprende, sconcerta, diverte, lascia interdetti. Da ritenere adattissima ad essere presentata in un festival.

– Augusta Franco Cardinali, Voce della Vallesina

Il De bello gallico di Nicola Campogrande ha fatto il suo debutto al Pergolesi lo scorso 24 novembre. Un’opera contemporanea che conquista uno spazio tra titoli di repertorio, firme di grandi compositori e tradizione.

– Giorgia Clementi, Capocronaca

Instrumentation

solo: sopr., ten., bar.

male choir

fl(picc).ob(eh).cl – hn.trp.tbn – perc (2) – harp – vln.va.vc.cb(e-bs)

Press

Duration 75′

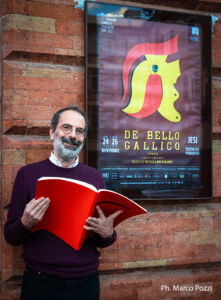

World Premiere

Jesi, Teatro Pergolesi

November 24 and 26, 2023

Giulio Prandi (cond), Tommaso Franchin (stage)

Published by

Breitkopf & Härtel

MM 2211103